Lulu, I know you miss home, even though you claim you don't. I'm sending you the items you requested tomorrow.

Your fridge abroad is stocked with ewedu, panla, snails, and green peppers from the African Grace Food Store. Yet, you say you miss going to Utako market to buy ‘real ones’. "They sell goat meat without the skin, and it doesn't taste like goat meat," you complained over a WhatsApp text.

Manchester can't be home without the food you know. And home is coming in a 12kg Ghana-must-go bag. It's the bond we share: you, me, and Nigeria.

I bought you roasted goat meat intact with the skin because it's a memory of taste, of home. I also packed egusi and iru for pounded yam.

Do you remember how I threw boiled yam slices into the mortar for your husband the Sunday before you left? He waited with the pestle in hand, ready to pound them into smoothness. Soaked in sweat, he adjusted his glasses on the bridge of his nose and panted, "Pappy, why do you always peel the head of the tubers? If they have lumps, it's not my fault."

Lulu, I know you're not trying to cook alone. You're trying to nourish your memory. Together, this becomes a ritual that binds us together through our bodies, through recreated memories across borders.

In Igbo communities, a protruding belly is considered a sign of honor and future wealth. In Ayobami Adebayo's debut novel, food is used as a symbol of hospitality in Yoruba culture. However, when Akin's mother visits Yejide to inform her about Akin's second wife, Funmilayo, chosen to bear children for Akin, she serves them spoiled beans out of spite. As a result, they have to make an emergency stop by the side of the road to defecate on their way home. Through this complex relationship with food, ethnic groups negotiate their identity and assert their differences from other groups.

Based on the ingredients you use and the flavors of your food, people can make assumptions about your ethnicity. Yoruba cuisine is well-known for its use of spices, especially pepper.

I am Ijaw, but I have lived in Lagos for most of my life, so my Port Harcourt cousins agree that I am also Yoruba. My Yoruba cousins mistakenly believe that I am Igbo, and most Nigerians make the same assumption because of my physical appearance. However, they quickly change their minds when they hear me pronounce words like "apple" as "happle."

I also enjoy pepper, sometimes too much. However, I cannot speak the Yoruba language without sounding like an outsider. This mother tongue that I understand every syllable of but cannot speak clearly without sounding ‘Oyibo’. The accent pours into my speech because the Yoruba vowels instruct you to breathe out before pronunciation.

If identity can be negotiated by how you look and what you sound like, what then happens to food and how you cook it? How does it speak of love?

In a previous letter titled "In Siegfried," I wrote about how I fell in love and how I cooked so much for the subject of my love. I wrote:

"At home, I would lie down on my bed, remember my day with you, and smile like a fool. I used to be content in those days. It was a love that was enough until it wasn't. My cooking for you was a love affair.

I packed so much food each day we met. I once told you that I had fried plantains and eggs all for you. My back started to hurt because of the extra weight in my bag, and I told myself it was because you weren't eating well. You had no time to cook, no time to care for yourself. It was a valid excuse."

As a child, my mother always packed my food for school, so I didn't understand why some kids brought food from Bukkas, especially when their parents did not have to wake up early. My cousins and I had to leave the house by 5:30 AM for our 45-90 minute journey to Shepherd Hill, beating traffic along the way.

The bus driver started by picking up the kids from the farthest away first, starting at our estate in Aso-Rock, Okokomaiko. In Ijanikin, we picked up Toyosi and her talkative brother. Then Chinenye (the girl who spat on and bit anyone who got into a fight with her), and Aswad (the boy with the highest punk hair I've ever seen, which once saved him from a serious head injury). His father was a friend of the family.

Next, we picked up Ifeoma and Osarentin, sisters who were in my class and my older cousins' class. I once had a crush on Ifeoma, but she was more into me. My true love was Tomiwa Odunsanya; we had an affair of rubbing legs under our desks.

Finally, we headed to Agbara Estate, where our school was located, and picked up the estate kids last: Ifeoluwa Odewunmi, her sister Ayo, Franklin the light-skinned boy, and Mariam Ejilasisi, who is now a doctor in training in Canada.

These estate kids were lucky. Their journey to school was faster, as they woke up at 6:00 AM or later, while I had been awake since four o'clock to catch the bus. With all the kids on the bus, we headed to our school on Lema Close in triumph.

In my early days at school, I started to recognize my favorite foods. For composition class, we were asked to write essays on several things, like our favorite foods. In my writing, I was conflicted. When my mother packed fried plantains and eggs, it was the best thing on the planet. When she cooked fried rice on special occasions and during festive seasons, I was in heaven. On school-cultural days, she took special care to prepare my native Ijaw food: yam or plantain pepper soup cooked with chicken or fish stock.

Eating my mother's delicious food was an important part of my childhood, and developing an interest in cooking it myself was a defining moment. My experiments began.

The first time I cooked, I must have been six. I stood on a stool, leaning over the pot of noodles. It was an experiment, and the kitchen was my playground.

One day, when my mother was late from work and my younger brother and cousin were starving, I decided to cook okra the way she had taught me. She had whispered the instructions in my ear, and my mind was a repository of them. After I added the grated okra, washed iru, salt, and a cube of Maggi seasoning to the pot of water, her voice instructed me from memory: "Do not cover a pot of draw soup," she said, her expression distant as she remembered. Her late grandmother had taught her too. "Covering the pot takes away the slime, you hear?"

She also told me that the secret to a tasty pot of porridge beans is a little salt, a lot of sliced onions, blended garlic and ginger, and burning it slightly. When it's done, scrape the burned bottom of the pot while stirring. Oral recipes like these are a type of storytelling passed down through generations. Instead of cookbooks, I got stories. I learned by watching, experimenting, and trusting my instincts.

In many cultures around the world, food is said to be the way to a man's heart. In Nigeria, single women who own Bukkas (local small restaurants) are known for their ability to attract and snatch husbands from their married homes. My mother told me that Bukka women wash their vaginas into food for juju to sweeten it. Oluchi's father insists that the juju is in the oil. In any form, it is superstitiously believed that these spells are often carried out to attract and retain their customers.

However, I believe that cooking to entertain like that is really hard work. At the Bukka, no matter how rude a man is, a Bukka woman must pet his ego. She must speak to him softly, laugh at his dry jokes, and give him more stew for his white rice when he barks at her. She must bring him water in a bowl to wash his hands before and after he eats. In between mouthfuls of pounded yam and egusi soup, he rants about his wife. He tops his food with beer and these women will wash up these stories from his lips in rapt attention. It is not their fault; it is business.

When they return home, in the absence of love and the reinforcement of the "woman-listen-to-me, I-am-the-man" status, these men are met with more stubborn and feisty women who will talk back. In their ignorance, they do not know that the home is not a Bukka; it is a place for love. Logically, I believe that these stories may have been fabricated and spread by an association of aggrieved wives who watched their husbands spend more time at the Bukka than at home.

Dry season. Farmers in Plateau, Kwara, and Benue plant peppers as a cash crop. Five months later, during peak season (October-March), they pick the peppers ripe but not fully mature as this yields the best flavour. The peppers are then packed in bags or baskets lined with paper or leaves to absorb moisture and prevent bruising, and shipped across Nigeria and abroad.

When I ran away from Okokomaiko to live with a relative at Isolo, I learned the patience required to stand in the kitchen for long hours cooking on multiple burning stoves. The small kitchen became an oven, and I was being cooked too, but on low heat.

One weekend, during the COVID-19 lockdown, I was with my cousin Moyo, who didn't like the kitchen much. I don't blame her because it's hard work. Her shoulders were sloped and hunched, a posture she exhibited when she was angry and irritated, but couldn't do anything about it. It made her look old and gaunt.

Her mother ordered her to straighten her face. "Why is your face like that?" she asked. Moyo said, "Nothing," and her mother threatened to pour a boiling pot of soup on her face. Still, her expression remained unchanged. "Put a smile on your face right now," this time an urge, a watered-down threat laced with a plea.

"Is this how you will cook for your husband? Come and learn so that when you go to your husband's house...When the food is ready, serve your brothers." These statements angered me, but in life, one eventually learns to always wear an appropriate face no matter the occasion, no matter what goes on inside you. When would she realize this?

In a house like that, where normative gender roles were clear-cut and hard and set, where cooking was viewed as a submissive, lesser role that was not to be negotiated between the sexes, I was also forced to contemplate my identity as a man there. Was I perceived as a lesser man? And if so, why? Were there other factors that contributed to this?

As I stirred the bleached palm oil mixed with sliced onions, pepper, and other spices with a cooking spoon, Aunty Tade said, "It is like you love cooking," and I replied, "No." I was burned out, but I didn't tell her this.

Cooking became a chore, and I lost my love for it in that kind of routine on-demand-entitled designated role. You can equally love something and hate it. What if a habit is mistaken for love? These hours of cooking against my will were my ten thousand hours. Cooking became something I did without thinking, muscle memory. Sometimes I cook as a way to cope and function because it is a conditioning.

I turned over the browned chicken parts frying on another burner, expecting a reply, but she was tongue-tied. Her statement was a means to an end, and my response was the end. She had made the statement, "It is like you love cooking," as a means to justify why I was always the chosen one to join the maid, Habeebah, in the kitchen, apart from my cousin who joined us occasionally. Perhaps she needed a yes to strengthen her excuse when telling her siblings, mother (our grandmother), and every other person who would listen.

Ogbono soup later went into that smoking pot. Another burner on the gas was filled with the tomato stew, and true to the stereotype, the pepper-to-tomato ratio mix was 7:3, respectively. Next, I sliced okra. On the floor, a kerosene stove was also burning with a pot on top of it. Egusi was to be made there.

I had learned to cook large portions of food at Isolo, but not much in terms of flavors. Armed with the oral recipes and instructions from my mother, Aunty Tade still boasted that I would be better now because I often watched her cook.

The truth is, I transformed the taste of their formerly bland stews and made the best egg sauce for boiled yam. My egusi was so good that it reached Port Harcourt through visiting relatives.

Deep down I knew that Aunty Tade did not agree with most of my methods. I tried to think of cooking her way in the future, away from this house, but the image refused to be summoned. It would not surmise.

Lulu, I am writing to you because you were the last family member I lived with. Because my mother was the one who taught me to turn off the heat under the rice only when I heard the sound of it sticking to the pot: tah, tah, tah.

But I am not trying to cook. I am trying to remember. Because I know that cooking is nothing without memory and the storyteller's mouth.

The time in your house. The yam porridge, slightly hard, and while chewing his food, your husband told me that the right time to add palm oil is when the yam is about to break into a paste.

The time when I was restless and cooked salty, dangerously peppery, tasteless, overcooked, and undercooked foods. The day I served you and your friends undercooked fried chicken. You dug into it to discover a redness under the flesh hanging to the bone. You called me into the sitting room, and the leftover chicken on your plate was discarded in pieces. "Why are you not patient?" you asked, spitting more chewed chicken into your plate. It was an act of correction, a chance to learn. I stood embarrassed, nodded, and cleared the plate.

When I returned to school after my internship, my friends became my guinea pigs for the Ofada sauce that I had learned from you. You made me run the market errands, so when I rode a motorcycle to Ipata Market in Ilorin, I didn't approach the sellers as a novice. I was not unsure of which peppers to buy—everything had to be unripe and green.

The time I prepared diced and fried plantains, vegetables sautéed in tomato sauce, and fried chicken. It was my final year of university, and exams were over. My roommate brought his friend, Rowan, the guy who had made it clear through his actions and body language that I was not up to par. We had had beef over Pentecostal school fellowship politics. The food was ready, so I switched off the electric stove and took a walk.

When I returned, Rowan was gone. I feigned ignorance and asked, "Where is your friend?" Of course, the emphasis on the word “friend" was an accusation. Why did you bring him? You know I am not comfortable around him. He doesn't like me. How dare you? Daven fired back with a question, "Where did you go?". I told him I took a walk, but he knew me better than that. I was always happy to give out food, but not in this case. “Tufiakwa,” the perfect Igbo word: over my dead body.

The time with fried rice—the one your husband did not eat at work, brought back his lunch plate full, and said, "I cannot eat it. The garlic is too much. My colleagues make fun of me. They know the smell of my food." I threw the food into the trash, washed the plates, and went to sleep in anger.

The time, alone in Abuja, in the glory of my previous employment, months after you and your family left for Manchester in the heat of the Japa-wave, I went to the market on Third Avenue, Gwarimpa with Ofada on my mind.

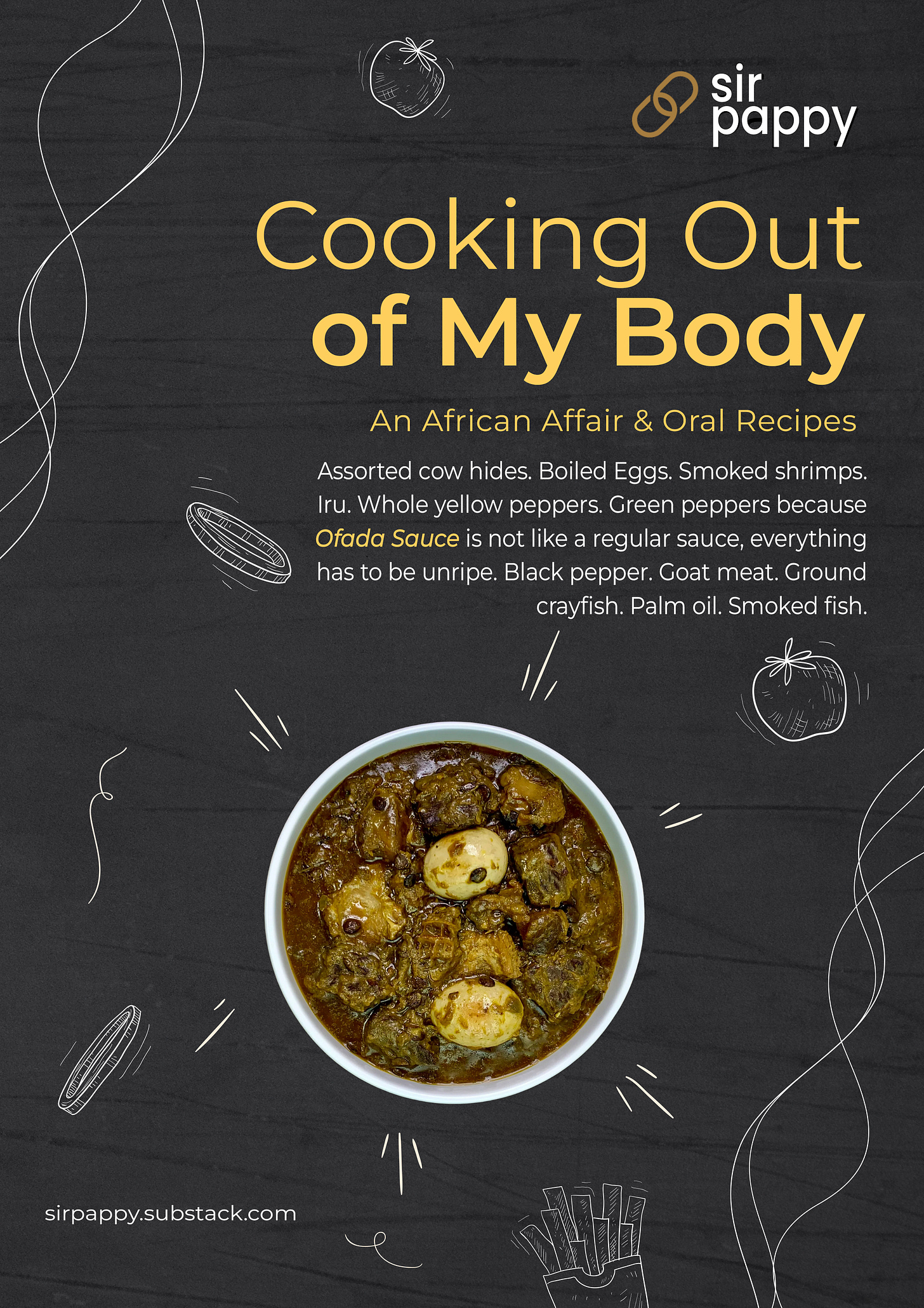

Ingredients: assorted cow hides, boiled eggs, smoked shrimp, iru, whole yellow peppers, onions, green peppers (because Ofada sauce is not like a regular sauce—everything has to be unripe), dry black pepper, goat meat, ground crayfish, palm oil, smoked fish.

Although you were out of reach, what you left with me was within my grasp. It was etched in my memory.

Recently, on a trip to Jos, a twelve-year-old sitting next to me on the bus asked me my favorite thing to cook. I hesitated and blurted, "Fried rice." His follow-up question was, "What else?" I added pasta, but deep down I felt unsettled and unconvincing.

Writing to you made me realize that my favorite foods are made with palm oil. You can adjust the flavor of your food by varying the amount of palm oil, how long you bleach it, and when you add it. If you add palm oil late to a dish, it will have a slimy texture. But if you bleach it as the first step in cooking, it will deepen the flavor of your food. Additionally, if you heat the palm oil over low heat until it covers the pepper mix and turns black, you can be sure that the pepper mix will fry evenly.

The kitchen is the place for stories, and cooking with you was my favorite thing to do. I'm washing the peppers in the sink, and the palm oil is heating up in a tightly covered pot. I transfer the peppers to the blender and turn it on. Although I've been using blenders for years, I'm never prepared for their loud buzzing. I cringe as the roar covers our voices like a blanket. You have to scream to talk, and I'm struggling to hear you.

"Aunty Bola was never my mother," you shout.

I turn it off after a few seconds. "What? Aunty Bola?" I ask, to be sure I heard you right. It remains a wonder that you and your siblings call your mother ‘Aunty’ like the rest of us. It's the worst kind of detachment. You pour the smelly, milky water from the iru you're washing into the sink. "She left me and my older sister with Sisi after her first marriage ended with my father and was having the time of her life..." Your voice trails off, and you sniff. I resume the blending, and we're quiet again except for the roaring sound.

I stop. Your face is wet with tears because you're slicing onions. "Aunty Bola cooked her way into the hearts of men. All her money went into that, and we were always hungry."

With you, it's easy to listen. "The secret is in the oil. If you get it right, half your work is done," you explain. Minutes after instinct-measured readiness, you slide the kitchen towel into my hands. "Will you take the pot to the back, Pappy?"

At the back, after a few minutes, you take off the lid to inspect the oil's clearness. "She always made duck soup. Have you ever eaten it? Is that not Juju? Duck soup is for catching men." You cough as the smoke gets into your nose.

When the smoke clears, you shake your head in satisfaction with the translucency. I understand. It's ready, so we return it to the stove and finish the cooking.

Sometimes, I dream of cooking for you in the kitchen on Jabi Boulevard, in Aunty Tade's kitchen in Isolo, or even our grandmother's kitchen in Okokomaiko. My mother says it is a sign of soul trade. That cooking for someone in your dreams is a sign of spiritual oppression and bondage, and that I need deliverance.

Lulu, when I cook Ofada sauce, I am cooking from my soul. I am fighting off nostalgia and my loss through your japa-migration. I still haven't rented my place, and I miss you, the house, and my room terribly.

Dede cooking in a friend's house he's house sitting for a month.

Writer: Dede Israel

Editor: Olachi Olua

This is so good ❤️

A beautiful read, as always. Enjoyed every bit of it. And picked up on a few cooking tips too, thanks!